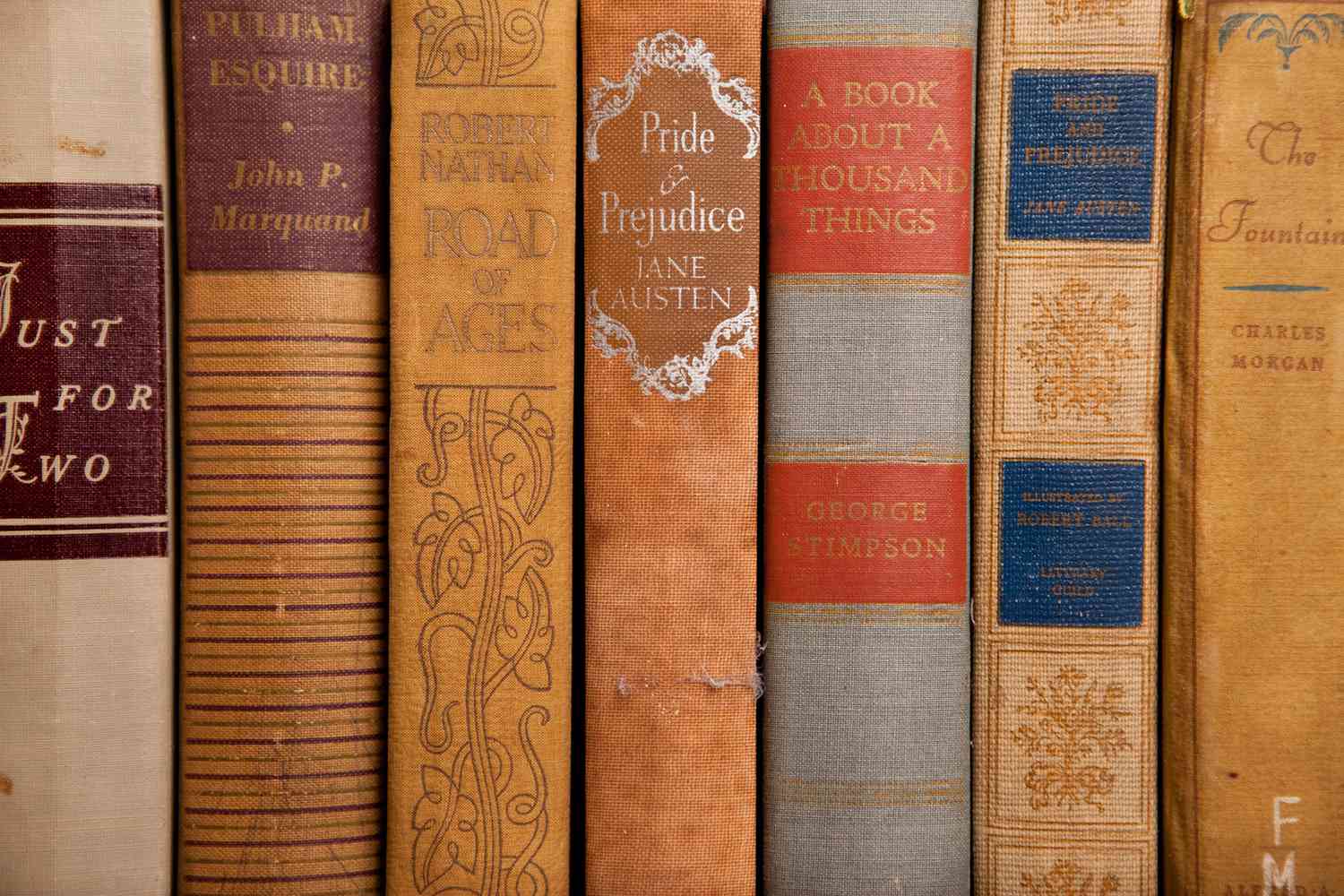

A “Classic” – note the capital ‘C’ – is described as something that has been “judged over a period of time to be of the highest quality and outstanding of its kind”. When it comes to literature at least, I have found that this seemingly complimentary term has come to mean something else – something rather more negative.

Image source: realsimple.com

“Who reads the Classics anymore?” “Why should I read a Classic?” “Classics are slow and irrelevant.”

If you have been shocked and saddened by such statements, you can consider me a kindred spirit.

The term ‘Classics’ in the literary sense is usually used to describe the works of the prominent European and American novelists of the 18th and 19th centuries. (Which is not to say that older works do not qualify, but in the interest of clarity I shall stick to the narrower definition for this particular write-up.) This was the period when the novel was still a relatively new art form, and the men and women of the day explored diverse themes and styles in their endeavor to bring their stories to the world. It is these themes that many younger readers (and far too many older ones) now dismiss as ‘irrelevant’ and these styles that are categorized as ‘slow’.

For me personally, the Classics have been an enduring love affair. It began when my parents brought home illustrated, abridged versions of books like Count of Monte Cristo and Treasure Island. I quickly found myself lost in the plot and the drawings depicting a world so far away, so fascinating, it might as well have been Middle-Earth. (Ironically I would read Tolkein’s work well after I was into adulthood, but that’s another story).

Image source: abebooks.com

From there to seeking out the originals of these works was but a step, and at the age of nine I fell headlong into the rabbit-hole with Lewis Caroll’s Alice in Wonderland, explored the moors of Kent and the streets of London with Pip Pirrip in Dickens’ Great Expectations, and chuckled with Bertie Wooster through the dangerous local politics of Market Snodsbury in Wodehouse’s Right ho, Jeeves.

Obviously, I gathered very little of Caroll’s allegory, even less of Dickens’ message and only a fraction of Wodehouse’s humour, but the important thing was that I enjoyed it nonetheless. Here were characters, not caricatures! A world apart, a world limitless, full of fantastic creatures, funny Aunts and haunting widows, where a rabbit carried a clock, a hare drank tea, a butler was the pillar of English aristocracy and a beautiful girl who was raised to ‘break men’s hearts’, broke not just that of the narrator of the story, but the reader’s too. Many years have passed since, and these Classics have spoken to me through my darkest hours and my happiest.

What is slow about the work of Dumas, where swashbuckling musketeers roam the streets of Paris and Calais, facing danger at every turn?

Or the work of Mark Twain, whose work can bring goose bumps to your skin, a laugh on your lips and a tear to your eye, all within a few pages?

Jane Austen’s social satire remains relevant long after the elegant society of which she wrote has vanished – after all, from Emma Woodhouse of Highbury and Aisha Kapoor of Delhi, is but a change of costume.

Emily Bronte’s Heathcliff needs no changes of costume or scenery – Yorkshire and WutheringHeights itself is immortal. When love is reduced to - and raised to - a primal force of nature, as she does so skillfully, it transcends settings and characters.

Dostoevsky’s Rodion Raskolnikov is very little removed from the Rashid Khan you might have passed in the street today – impoverished, brilliant and teetering on the edge of a moral breakdown, which will lead eventually to Crime and Punishment.

And poor Tess, Hardy’s Tess Durbeyfield, a character who deserved all the love the world could give her, and got only lust and neglect – a story that is repeated every day in every village, town and city.

Looking back on it, these books shaped me in profound ways. Oliver Twistmade me question the accepted realities of urban poverty, Tess of the D’Urbervilles made me debate the hypocrisy of conventional morality and Anthony Trollope’s Phineas Finn made me laugh at the puffed-up arrogance of politicians.

The key to the relevance of the classics, then, lies in the definition itself. “Judged over a period of time”, it says– and that’s exactly what these books are. They have survived, not because they were preserved by kindly archeologists, but because they spoke of the human condition. The greatest literature, as a somewhat more modern great, William Faulkner puts it, is ‘about the human heart in conflict with itself’.

It is this conflict that gives us the protracted revenge of Edmund Dantes in The Count of Monte Cristo, Jane Eyre’s abandonment and eventual return to Mr Rochester, Ahab’s single-minded, hopeless campaign against Moby Dick, the gradual descent into penury and death of the Mayor of Casterbridge. And why go even to such extremes? The Duke’s Children, the last of Trollope’s Palliser novels, deals extensively with the relationship between a loving father who has been distant from his children throughout their childhood. Now that they are older, showing a penchant for not doing quite what they would be expected to do, he finds himself at his wit’s end – and if that is not a dilemma faced by fathers to this day, go ahead, call me a liar.

Never mind, then, that islands of fabulous, undiscovered wealth no longer exist. That men do not sell their wives in games of chance (well, not often, but it’s been known to happen if you read the vernacular newspapers), or that whaling is banned.

Image source: www.indypl.org

As long as there is humanity, we will tell these tales, over and over, because they are our own stories. Perhaps they have already written your story too, those dead men and women, long since buried or turned to ashes. They have told it, in some form or the other, in stately homes or scorching deserts, on board a ship or in a Siberian prison camp – you have lived already in their imaginations. Ignore their beauty, ignore their message, and denigrate them if you will. The loss is your own.

Comments