1. A Good Night’s Sleep

“Here, Chhamiya, chal aaja,” Bholu said as the canine bounded across the green of the night and started devouring her dinner of two chapatis with a bit of mutton thrown in. He looked up at Charan Singh and added, “Looks like you haven’t fed her properly.”

“Nah,” said Charan, “There are days when she won’t eat properly in the day and then become baavli at night” and he laughed. He looked at the canine with a bit of wonder and admiration. Amazing how some of these country dogs grew up to two feet in height. “Here, have a beedi.”

They lit up, while seated on the charpoy outside the shed park and talked of many things—Bholu’s aching knees, Charan’s new grandson in his village, how the new Doctor babu in the clinic had cured Charan’s piles in a matter of three days, and the price rise in their favourite beedi, and whether Suhani, their favourite maidservant in the neighbourhood, would come back before Holi. It was well past eleven and the streetlights of the city of Mumbai were taking over the road from the pedestrians and late-night traffic. They talked for about an hour and then with a rheumatic grunt, Bholu got up and shuffled across the park towards the exit. He then walked the kilometre and half across to his own municipal park, took a piss in the park grass, filled the empty Coca Cola bottle with drinking water, and tossed and turned over in his bed a bit, and went off to sleep.

Bholu Ram was fifty-five years old. For the last twenty-five years, he had worked as a municipal watchman at one of the parks in a Mumbai suburb. The pay was okay—fourteen thousand per month—and moreover, the job came with a large shed in which he could sleep at night. That shed was his luxury, because at night he could even have his fix of ganja there or play cards with Charan when he wanted over a bottle of liquor. Opposite it was a smaller shed, used to store buckets, ropes, plastics, and whatever the babus at the City Corporation had wanted. Bholu had never married. At the age of thirty, he had come to Mumbai, like millions before him, looking for a job. Fate took a hand, and the first job he had found was as the watchman of the municipal park, where his duties included watering the grass, co-ordinating the activities of the sweepers who came with their trucks, shooing errant stray dogs away, and mostly watching boys play cricket, pensioners take walks, ladies do aerobics, and young collegians smooch on the benches when they thought no one was looking. His sole friend in the city, Charan, did a similar job at the other park, and they would meet every other day.

It was the day of Holi. The park was littered with deflated balloons all over and colours had shaded the ground and benches with the spirit of festivity. In the morning, people from the neighbouring apartment blocks had arrived, like they did every year, to play the traditional Hindu festival of colours. They had thrown water balloons and coloured powder at each other, shouting and screaming to get out of the way, when in reality all of them had wanted a sound dunking and more colour everywhere on their bodies. That too was available—the hose pipe and buckets from the shed had been used liberally and they had finished by late morning, looking like people just out of a Halloween party. Things did get a little rough—Bholu saw Mr Srivastava holding Mrs Srivastava by the shoulders, while her friends had poured one, two, three buckets over her, as she gasped and spluttered for breath. And, Rajan Saab had cried blue murder when he was rolled in the mud by his colony friends, till he emerged brown and just a little angry. Even the hose pipe had not improved his complexion much—that would take a day or two. Bholu smiled to himself—what was Holi without a little mischief, a little wrongdoing? He knew they—the men and women from the neighbouring buildings—would go home and sleep till the evening and then probably get together to booze into the night. It was said Holi was the day to make friends out of enemies, because you were forgiven your little sins and you could start all over again. It was a sort of mini baptism by water, and colour. Playing colour with friends, almost anything went in the name of baptism, he thought wryly. Bholu reminisced about the wild Holis he had played in his native state before coming to Mumbai. That seemed so very distant now.

He dozed off by mid-afternoon, dreaming about his little village.

He was woken up by a scream and the sound of shouting. He opened his eyes and got up from his charpoy in the shed. Through the window he could see three boys, all in school uniform, and a couple of girls. One of the girls was drenched in blue ink and colour, and crying, while the other tried to console her. They could not have been more than fourteen or fifteen.

He walked out and asked a man sitting on one of the benches, “What happened?” The man said, “Kids playing after school. One of the boys did masti with that girl and she shouted back at him. She slapped him. And then he slapped her, twice, while his friends laughed. That’s when the girl screamed.”

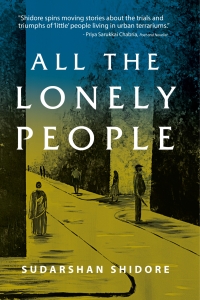

About the Author

Comments