At 44, Rangan Chakraborty was grappling with who he was. He looked down longingly from the balcony of his 8th floor plush apartment at the road beyond the walls of his community garden. There were people thronging the straw-roofed tea stall sitting on the benches laid out in the front. Some kids were engrossed in gully cricket.

He looked at the china cup sitting on the glass top table in the balcony and longed for the mud cup, the bhar, that made him feel so much at home. He loosened the tie around his neck, it felt like a noose at times.

He looked down again and could see himself right there sipping tea with the locality boys talking about football and politics. Playing cricket and cycling around. That world still existed right in the next lane where his old crumbling house stood but he had moved on into this new upmarket community, up the ladder of success, up a road where material acquisitions defined him and all that remained was the longing for that cha in the bhar.

The intercom rang. “Sir, some people want to see you from Keshtopur Milan Samity. Should I send them up?”

Keshtopur Milan Samity was located in the lane where he had left behind his childhood and youth. The club was in yet another dilapidated room where the locality men and boys played carom with gusto under the swinging light bulb, watched Mohun Bagan – East Bengal matches on the small TV and screamed their lungs out. This was the room from where the Durga Puja and blood donation camps were organized and education for poor children were also sponsored. This was also the room where women came to for help if their husbands were beating them up. A few words from the heads of this organization often ensured peace for the parar nirjatito bouma (locality’s harassed daughter-in-law).

Puja was months away so there was no question of asking for a subscription, Rangan wondered why they had come to meet him. He told the security to send them up.

Two men walked into Rangan’s 1500 square feet apartment. Rangan had known them as Asit da and Bhombol da all his life. Asit da would be around 60 and as far back he could remember, he had owned the photocopy shop around the corner. Bhombol da would be around 50. He was in some government job but would be home sharp at 4pm and would be by the carom board at the club by 4.30pm.

They both sat tentatively on the edge of the sofa, scanning the rest of the furniture intensely.

“Rangan, we have come with a request,” said Bhombol da.

Rangan’s eyebrows creased involuntarily. He was now sure they wanted money.

“We are running a signature campaign. That liquor shop inside the Keshtopur Bazaar is a menace. Every other day there is a drunkard walking out and creating a nuisance. We want to shut down the shop. For that we will need at least 500 signatures. Can you please sign and get your community people to sign too?”

Rangan’s face had turned ashen. He could feel the ceiling reeling above him. He closed his eyes to steady himself.

“I am coming down with a fever. Can you talk about this some other day?” He said.

Both the men looked concerned.

“See a doctor immediately Rangan. Lot of Dengue cases in this area. We will come back later.”

They hurried off.

Rangan sighed. But how long would he be able to keep them away?

*

On Sundays Rangan felt alive. Not solely because he didn’t have to put the noose around his neck, drive his car through the traffic and do “Yes, sir” all day long. He felt happy for a different reason altogether. On Sundays he was out of the house by 5pm in a pyjama and short kurta long before his wife woke up from her afternoon siesta and could rebuke him about the lack of class in his attire. He took two plastic bags and headed for the Keshtopur Bazaar. He bought fresh vegetables digging his finger into the skin and pressing below the gills of the fish to check for its freshness, just the way his father had taught him. Then he left his overflowing bags with the vendors after paying them and vanished into a dark alley.

He came to a shabby door that had been just opened. He settled on an equally shabby bench, rubbing his fists together in anticipation. He was handed a liquid that looked like Limca in a half-washed glass that was much smaller than a normal glass. He gulped it down and quickly took off on an emotional journey through college, through the bylanes of Keshtopur, through the heady feeling of falling in love, through the pain of losing it and then with each glass he felt he went back to being the Rangan of Pal Para and he ceased to be the Rangan of Palazzo Heights.

He walked out of the shop and quickly emptied two packets of Paas Paas into his mouth, picked up his bags and headed home.

“Rangan! Rangan!”

Someone was calling him from behind.

“Are you okay now?” asked Asit da.

“Why? What happened to me?”

“You had fever that day.”

“Oh yes. I am fine.”

“Good. Then sign here.”

He brought out a sheet of paper with signatures scribbled on it.

Rangan sprang backwards like he had encountered a leper.

“You are still at it?” he asked angrily, surprising Asit da.

“You know because of us this locality has always been safe and trouble free.”

He held up the pen.

Rangan held up both his hands showing those were occupied by the heavy bags.

The smile on his face had a faint mark of victory.

*

Rangan knew on a Sunday morning his wife stayed in bed late. After his breakfast and a shower he had this strange urge for a bhar of cha. Or did he actually want to find out what was actually going on about the liquor shop?

“How many signatures have they got?” he asked Poltu, the teenager serving him.

He quickly looked up at his balcony to see if by any chance his wife had come out for a stroll. For her, having cha sitting on that bench was the most classless thing to do. He didn’t want a demotion in her hierarchy of things the moment he reached home.

As such the familiarity shown by the gateman at Floriana Restaurant on Russell Street during one of the Puja days hadn’t gone down well with her. He had taken his family out to Park Street for dinner and after trying to find a parking, he came near Floriana hoping to find one. That is when the gateman had appeared out of nowhere and even before he could say anything, had assured him: “Your usual parking space is available Sir.”

He salvaged the situation by saying that he had client meetings there but he was sure he would have been guillotined right there if she knew that members of their old theatre group met there every month and drank like fishes. He was the only one who always emerged sober from the restaurant because he could not risk a divorce by going home drunk. Both their salaries went to the monstrous EMI of Rs 50,000 every month.

“Dada, they have got almost 400 signatures,” Poltu’s voice broke his thoughts.

“400 already!!” Rangan said alarmed.

*

It was a Sunday but Rangan was sulking. His wife wanted to go to the bazaar with him and pick up the best ilish because her parents were coming for dinner. No matter how much he tried to convince her that he would pick up the best for them she remained adamant that she would go with him.

Finally he said, what he thought, would deter her.

“Classy ladies don’t go to the bazaar.”

“No?” she asked unsure.

“Okay, you get the fish but let me come to the supermarket with you. I will pick up some other stuff.”

Relief washed over Rangan’s face. He wouldn’t have to miss his weekly rendezvous.

“Boudi, how are you?”

Bhombol da greeted Rangan’s wife the moment they stepped into the supermarket.

Although he was older to the lady, but calling her Boudi, elder sister-in-law, meant giving her respect.

“Can you sign on this now?” Bhombol da promptly took out the paper.

Rangan’s wife looked aghast.

He gritted his teeth.

“You have still not signed this paper? Do it right now,” she said in a commanding tone.

Then she mumbled to herself, “I hate drunkards.”

“Thank you Rangan. Somehow we were stuck at the last signature. You made it easy for us.”

Rangan sighed. He had this strange feeling, like in Kalidasa’s story he had just cut the branch he was sitting on.

*

Two weeks later when he hurried down the dark alley he came to a closed door. He knew the door would never open. Behind those closed doors the Rangan of Pal Para was lost forever.

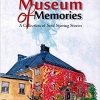

Amrita Mukherjee's latest book is Museum of Memories, a collection of 13-soul stirring short stories. She has worked in publications like The Times of India, The Hindustan Times and The Asian Age in India and she has been the Features Editor with ITP publishing Group, Dubai’s largest magazine publishing house. An advocate of alternative journalism, she is currently a freelance journalist writing for international publications and websites and also blogs at www.amritaspeaks.com

About the Author

Comments