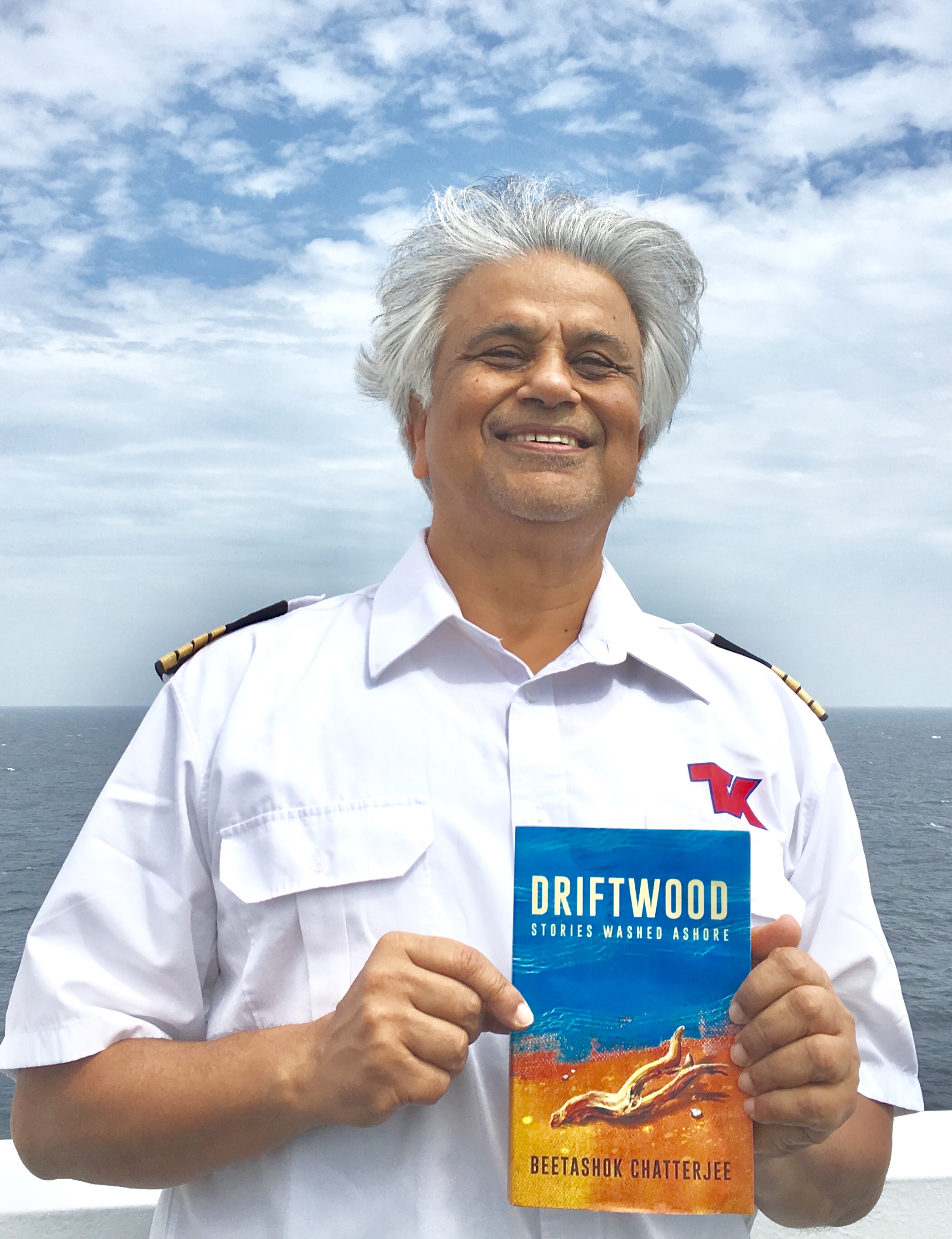

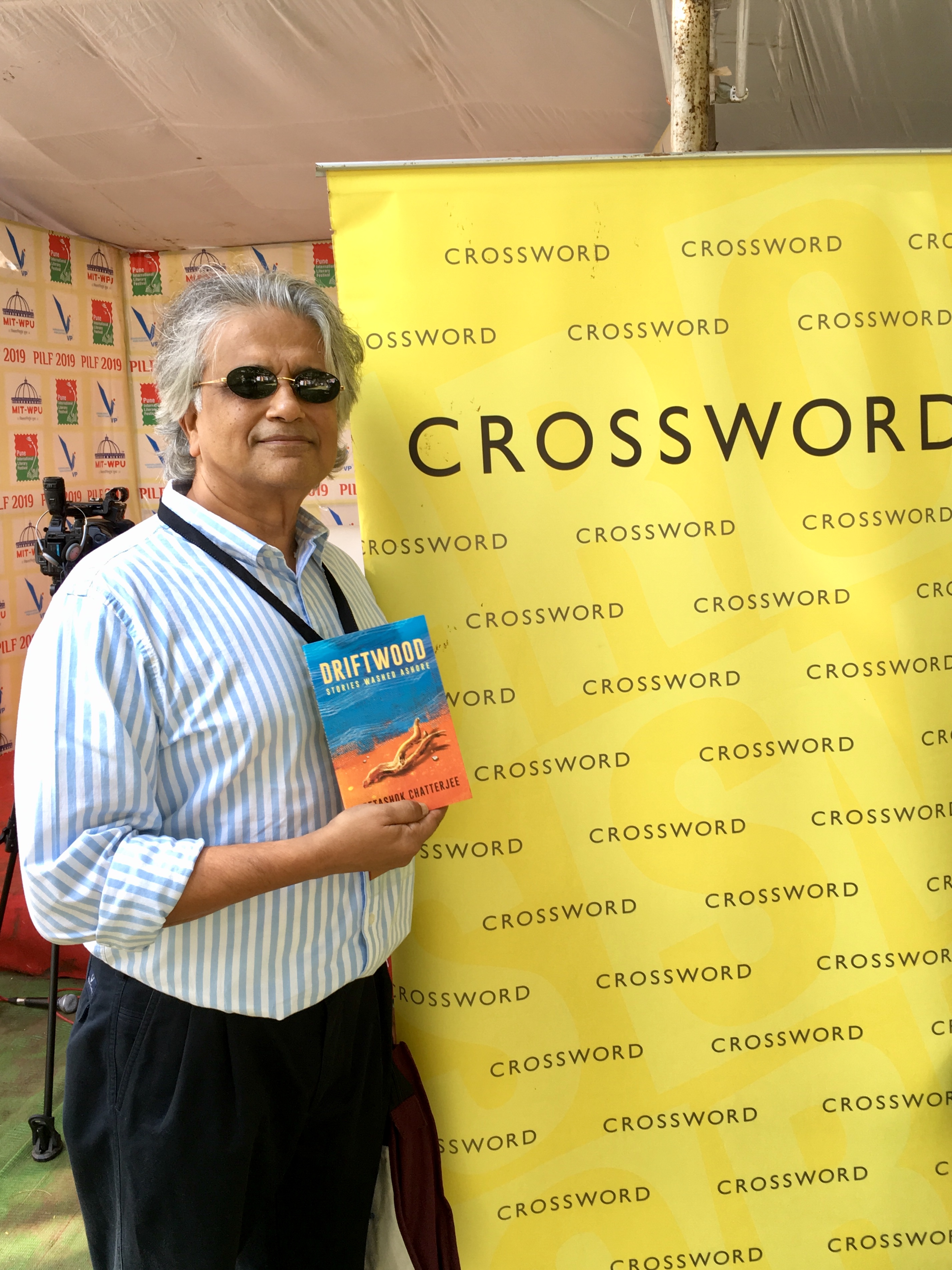

Driftwood: Stories Washed Ashore is a collection of twelve modern sea stories, but not necessarily for the seafarers alone. These are tales of adventure, intrigue, love, piracy and essentially of human nature. Beetashok Chatterjee has been at the sea for forty years and these stories are his maiden literary foray. In an interview with our Managing Editor, Indrani Ganguly, he opens up about writing, the sea, and this book.

Driftwood: Stories Washed Ashore is a collection of twelve modern sea stories, but not necessarily for the seafarers alone. These are tales of adventure, intrigue, love, piracy and essentially of human nature. Beetashok Chatterjee has been at the sea for forty years and these stories are his maiden literary foray. In an interview with our Managing Editor, Indrani Ganguly, he opens up about writing, the sea, and this book.

Indrani: Driftwood is a collection of very entertaining and thoughtful stories of and about sailors. Tell us Beetashok, does the ocean play a catalyst in your creativity?

Beetashok: Thank you for saying that. If you found it entertaining and thoughtful, then it looks like I have succeeded in my objective. Yes, that was the plan.

The ocean is a beautiful, tempestuous, vast source of inspiration. To see it in all its moods and colours according to the time of the day, season or the state of weather over the last so many years have awakened the poet and writer in me. (Yes, I’ve written more than 40 sea poems as well!) Moreover, the long voyages across the oceans gave me the time and peace of mind to organise my thoughts, draw from my experiences and those of others, form coherent storylines and put them on paper. Yes, the ocean is a catalyst for my creativity.

Indrani: There is a general perception of merchant sailors leading reckless and flashy lifestyles, being womanisers too. Is that correct?

Beetashok: (Smiling) You forgot to mention drunkards, liars and losers—yes, all of the above! But seriously, those days are gone. If it was true once, it is no longer so. International regulations and the demands of the job have put paid to all our freedom and fun. They have become so stringent that it is now survival of the fittest. One has to toe the line if one wants to keep one’s job. Most shipping companies do not allow any alcohol on board for the crew nowadays. Thanks to 9/11, shore leave is severely restricted in most countries. There is CCTV camera in the public spaces onboard most ships, from where 'Big Brother' in the Head Office can watch you live. The seaman of today is straitjacketed, walks with blinkers on and lives in fear.

I am fortunate to have seen some of the ‘good, old days’—those days which inspired so many ‘ripping good yarns’ in literature and Hollywood movies. (Sadly, Bollywood has taken no interest in sea life—Salman Khan as an M.Navy officer in ‘Bharat’ doing dance moves atop the cargo hold of a ship is testimony of this.) My story, ‘Transition’ has tried to capture this—how shipping has changed over the decades. That story is very close to my heart, for I am both the grandfather and the father of that boy who wants to listen to sea stories. The grandpa is the typical sailor you refer to, and the father is the kind of sailor one is now forced to become. I’ve seen those changes take place before my eyes. I came out to sea in the 70s, and am still sailing. It was pretty wild then, pretty tame now. I can only imagine what it must have been like before my time in the 50s and 60s!

Indrani: You have in one of your stories written a recurrent line: ‘He was just a seaman.’ There is a lot of pathos in that line, almost as if seamen are misunderstood perennially.

Beetashok: Absolutely true. Seamen generally are mistreated by one and all, never given their due respect. If you didn’t have seamen, you wouldn’t have worldwide trade. There would be no transportation of millions of tons of goods and raw materials by ship across thousands of miles every day. Economies would collapse. (There is no substitute for shipping—not yet anyway.)

Starting from the crewing agencies where you’re kept waiting for weeks before they give you a ship, to the visiting company superintendent who shouts at you because he can. From the Port State Control officer who boards just to find fault so that he can detain your vessel and exhibit his petty power, to the ship supplier who will supply substandard quality of provisions because he knows he can get away with it since he is appointed by your Company. From the hookers and charlatans who take you for a ride in the waterfront bars to the fair-weather friends and distant cousins who touch you for loans they never intend to repay. Seamen are simple, gullible folk who work hard in difficult conditions for their living, who’re not too familiar with the ways of the world and fall in love with whoever is nice to them.

Indrani: Would you have been a different person if you were not a sailor? Does the sea calm you or make you more philosophical?

Beetashok: I think so. When I was in college, there were just a few career options – doctor, engineer, civil services, lawyer… that was it. Luckily this sea career came along and made me the person I am today. I love being at sea, love being a tiny speck on the vast ocean. Yes, it calms me down and gives me the time and solitude I need for my creativity. Otherwise, Driftwood would never have happened.

Indrani: In the story ‘Little Girl Lost’, you have written about a young Filipino girl who joins a merchant vessel as a Deck Cadet. Tell us, how difficult is it for a woman to adjust in a ship full of rowdy male sailors? What is the role of the Captain in normalising things for her?

Beetashok: It is not easy. Men are the same everywhere. Be it Hollywood, Bollywood, politicians, the corporate world—sexual harassment takes place everywhere. Why should a ship be any different? Having said that, the good shipping companies have strict laws against sexual harassment, where a seaman will be dismissed instantly if found guilty of it. The Captain has a tremendous responsibility to ensure that women are respected on board and gender equality is maintained. Otherwise, any misdemeanours reported to the Head Office will ensure his dismissal too.

So, if you’ve got them seamen by their...ahem! cojones, then their minds and hearts will follow. Guaranteed.

Indrani: In the vastness of the ocean where the only human connect are your fellow sailors, even a winged visitor can stoke the interest and caring attitude of sailors, as portrayed in one of your stories. How much do you pine to get back to the general civilisation when you are in high seas?

Beetashok: Personally, I don’t pine at all, because what you call civilisation, I find crowded, polluted, dusty and sweltering with cunning, rude people. (I don’t mean family and friends, in case they’re reading this!) I’ve been sailing for far too long to be homesick. And now, thanks to technology, one is in daily touch with the family back home. But I can’t speak for every sailor on my ship or at sea. To each his own. Yes, it’s perfectly natural to miss one’s loved ones back home. But almost all companies are offering free wifi for their crews to utilise social media. So suck it up and quit pining, guys!

Indrani: You’ve been sailing for over forty years now; you’ve seen the old school ways of navigation as well as today’s cutting edge maritime technology. Is there any inherent difference between the sailors of yore and the ones today?

Beetashok: A vast difference, not just in technology. To the sailors of yore, the sea was a way of life. They would remain at sea till they were too old to step on the gangway for one last time. They would itch to be back at sea smelling the sea breeze after a couple of months on land. To today’s sailor, it is just a job to earn enough money to buy a house and get his sister married before calling it quits and doing something else ashore. But, to be fair to the new generation, sea life isn’t what it used to be. There is no freedom, very little fun—it’s like living in a comfortable jail for months and months at a stretch.

Indrani: You are such a talented storyteller and it is evident that one of the reasons for this is because you are a keen observer of life. Do you have storytelling sessions when you are free on the high seas? Do you keep a diary to write little nuggets of stuff that interest you as and when they happen?

Beetashok: No—I don’t have any storytelling sessions on board. I keep my profession separate from my hobby and don’t blow my own trumpet. In any case, I don’t think anybody is interested in my stories, though these are the people I wrote this book for. The problem is that social media has destroyed any reading habit that may have been inculcated in these youngsters while they were still studying. There are very few officers I have sailed with who read and who I can have a conversation with. Sad but true. In fact, till this book was released, few shipmates knew I’d written one. It is selling mainly among landlubbers.

Yes, I do keep a diary of sorts. I started keeping a journal as a young officer way back in the late 70s to jot down my thoughts and my experiences—not necessarily sea-related. Those entries have proved invaluable in the making of Driftwood.

Indrani: You have written about pirates. What prepares you mentally when you sail through the risky channels? Does a piracy episode scar a sailor for life? What then makes him come back to the sea?

Beetashok: Piracy is horrible. We are not allowed to carry arms to defend ourselves; nor are we trained to do so. Totally at God’s mercy! I have been chased and hounded by pirates once or twice, but luckily I managed to prevent them from boarding. I shudder to think what would have happened to us had they managed to come aboard. The Tom Hanks movie ‘Captain Phillips’ is, I think, a pretty realistic depiction of the problem. Yes, the trauma of being captured by pirates can scar one for life. I don’t think those sailors come back to sea ever. It’s only the rest of us who do, to earn our daily bread. Indrani: Tell us about the feeling of brotherhood among fellow sailors.

Indrani: Tell us about the feeling of brotherhood among fellow sailors.

Beetashok: When we’re living together for many months isolated from the rest of the world, we tend to develop bonds amongst ourselves. It’s just us against the rest of the world—against Nature, against the pirates, against anything or anyone who could disrupt our peace of mind or threaten our existence. Caste, creed and ethnicity are forgotten in our own little world. Seamen are simple folk, as I mentioned earlier. It doesn’t take us long to trust our fellow shipmates. Many friendships formed at sea stand the test of time.

Indrani: Are there lesser distractions while sailing? Do you think and write more when at sea?

Beetashok: Yes to both. For those so inclined toward creative work like writing or painting or composing music, there is no better vocation. I thank my stars that I have a job which allows me to indulge in my hobby while earning for my family at the same time. I definitely think and write more at sea. The routine life, not having to worry about your next meal or your laundry, no one to disturb you after hours—it’s perfect. I can’t see myself having these privileges at a shore job. I say this from experience; I did work ashore in Delhi for 3 years from 2001 to 2004 before running back to sea. I’m not cut out for that.

Beetashok's book of ripping good yarns is available online and in all major bookstores.

Comments